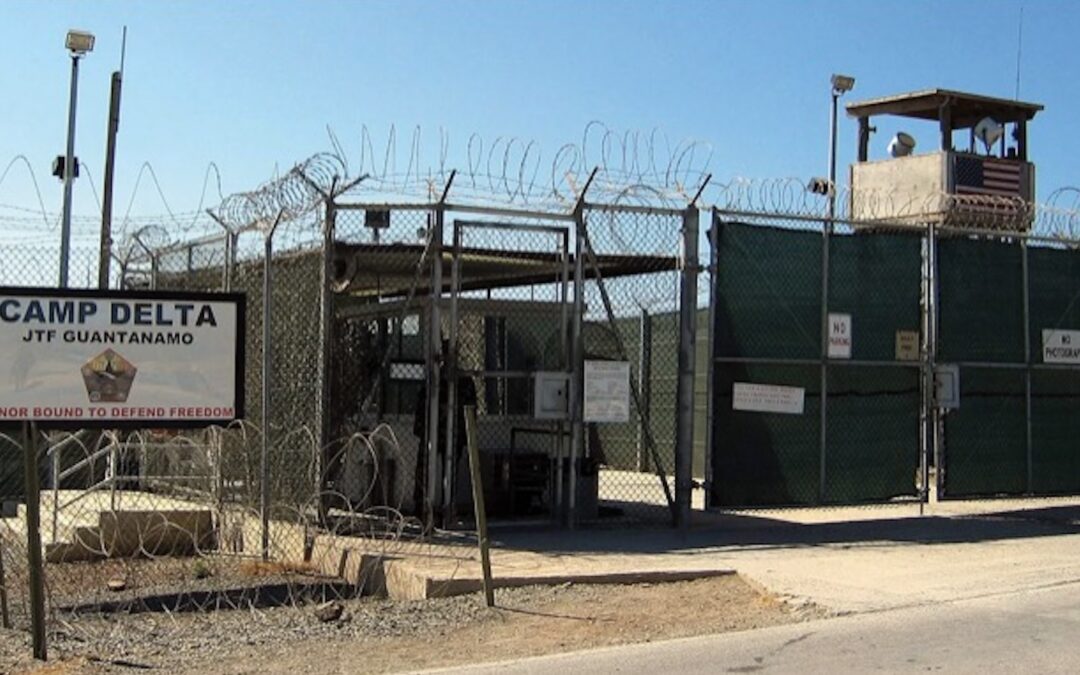

Good news and Guantanamo are two ideas not normally associated with one another, but February 2023 has been a month of important positive developments for the men being held at the Guantanamo detention facility and for eventually ending the failed system of military “justice” being used on the Naval Base to try men who have been charged with crimes.

On February 1, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the counter-terrorism and human rights, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, announced she had come to an agreement with the U.S. government to visit and review practices at the Guantanamo Bay detention facility. Here technical visit will include meetings in officials in Washington D.C. followed by a four-days spent at the U.S. Naval Station Guantánamo Bay, Cuba where she and her team will talk with detainees and military personnel. Over a three-month period, Ní Aoláin will also interview individuals in the U.S. and elsewhere, on a voluntary basis, including victims and families of victims of the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks and former Guantanamo detainees in countries to which they have been repatriated or resettled. At the conclusion of her mission, Special Rapporteur Ní Aoláin will issue an end-of-mission report on her findings and recommendations to address violations of human rights and international law.

Then on February 2, Majid Khan, who had been detained for nearly a year more than the sentence he received from senior military officials in October of 2021, was finally resettled to Belize, where his wife and daughter will join him. Khan was captured, in 2003, forcibly disappeared by the U.S., imprisoned, and tortured at overseas “black sites” operated by the Central Intelligence Agency, before he was brought to Guantanamo September of 2006. Khan pled guilty, in 2012, to war crimes including supporting al Qaeda by transferring money to individuals who carried out terrorist attacks in the years after 9/11. Although he completed his sentence in March of 2022, Khan remained at Guantanamo. In June of 2022, he filed a case in federal court, Khan v. Biden, challenging his continued imprisonment. The government never responded to the merits of Khan’s filing but arranged his resettlement in advance of a court-ordered deadline to do so. Read more about the many years of Khan’s legal challenges to Guantanamo justice.

The same day that Khan left Guantanamo, Theodore Olson, who coordinated 9/11-related litigation for the Bush administration and who is himself a 9/11 victim family member, became the highest-level member of the Bush Administration to acknowledge publicly the fundamental failure of the Guantanamo military commissions to deliver justice and accountability for the crimes of 9/11 and other terrorist acts. As Olson, who served as the 42nd solicitor general of the United States from 2001 until 2004, wrote in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece, “we made two mistakes in dealing with the detained individuals at Guantanamo. First, we created a new legal system out of whole cloth…. [T]he commissions were doomed from the start. We used new rules of evidence and allowed evidence regardless of how it was obtained. We tried to pursue justice expeditiously in a new, untested legal system. It didn’t work.” The second mistake was to pursue the death penalty in the newly created commissions, Olson continued. Although federal courts could have handled the cases 15 or 20 years ago, he concluded, that today, “the only guarantee that federal court prosecution brings is years of appeals resulting from the legal morass of the past two decades. This is no resolution…. The American legal system must move on by closing the book on the military commissions and securing guilty pleas.”

As the month drew to a close, on February 23, the Rabbani brothers, were returned to Pakistan after spending 20 years at Guantanamo without ever being charged with a crime. Although Pakistani by nationality, the brothers were born and raised in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, and are ethnically Rohingya. They were captured by Pakistani security forces in 2002 and then held at a CIA detention site for 550 days before being taken to Guantanamo in 2004. The younger of the two brothers, Ahmed, became well known for his artwork and also for his participation in the hunger strikes Guantanamo detainees have mounted. The Pentagon recently partially lifted its ban on the release of detainees’ artwork, but it is unknown whether Ahmed was able to take the more than 100 paintings he made at Guantanamo with him to Pakistan.